The Most Important Thing by Howard Marks

Rating: 9/10

Amazon link (note: This is an affiliate link)

Overview: A great set of principles for someone interested in investing. Pretty accessible for someone with a basic knowledge of investment/finance.

Howard Marks is the founder and chairman of Oaktree Capital. I started reading his memos after listening to him on The Tim Ferriss Show. He’s able to capture insight succinctly and without jargon, which I love. The book was over my head at times, given that I don’t work in investing, but it’s a must-read for someone who does (especially if you’re a value investor like Marks).

Marks found himself saying “The most important thing is X” to clients over and over, realizing there were several “most important things”. Each chapter title is one of those. So without further ado, select quotations from The Most Important Thing.

Introduction

I like to say, “Experience is what you got when you didn’t get what you wanted.” Good times teach only bad lessons.

Second-Level Thinking

Investing, like economics, is more art than science. And that means it can get a little messy.

First-level thinkers think the same way other first-level investors can’t beat the market since, collectively, they are the market.

Understanding Market Efficiency (and Its Limiations)

In theory there’s no difference between theory and practice, but in practice there is.

-YOGI BERRA

My son Andrew is a budding investor, and he comes up with lots of appealing investment ideas based on today’s facts and the outlook for tomorrow. But he’s been well trained. His first test is always the same: “And who doesn’t know that?”

[Market] efficiency is not so universal that we should give up on superior performance. At the same time, efficiency is what lawyers call a “rebuttable presumption”—something that should be presumed to be true until someone proves otherwise. Therefore, we should assume that efficiency will impede our achievement unless we have good reason to believe it won’t in the present case.

The image here is of the efficient-market-believing finance professor who takes a walk with a student. “Isn’t that a $10 bill lying on the ground?” asks the student. “No, it can’t be a $10 bill,” answers the professor. “If it were, someone would have picked it up by now.” The professor walks away, and the student picks it up and has a beer.

Value

But don’t expect immediate success. In fact, you’ll often find that you’ve bought in the midst of a decline that continues. Pretty soon you’ll be looking at losses. And as one of the greatest investment adages reminds us, “Being too far ahead of your time is indistinguishable from being wrong.”

Value investors score their biggest gains when they buy an underpriced asset, average down unfailingly and have their analysis proved out. Thus, there are two essential ingredients for profit in a declining market: you have to have a view on intrinsic value, and you have to hold that view strongly enough to be able to hang in and buy even as price declines suggest that you’re wrong. Oh yes, there’s a third: you have to be right.

The Relationship Between Price and Value

Investment success doesn’t come from “buying good things,” but rather from “buying things well.” [Marks talks about this a lot throughout. There’s no asset so good that it can’t be overpriced.]

People should like something less when its price rises, but in investing they often like it more.

The convergence of price and intrinsic value can take more time than you have; as John Maynard Keynes pointed out, “The market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.”

Understanding Risk

Especially in good times, far too many people can be overheard saying, “Riskier investments provide higher returns. If you want to make more money, the answer is to take more risk.” But riskier investments absolutely cannot be counted on to deliver higher returns. Why not? It’s simple: if riskier investments reliably produced higher returns, they wouldn’t be riskier!

[A rebuttal to the notion by academics that risk is merely volatility]: Rather than volatility, I think people decline to make investments primarily because they’re worried about a loss of capital or an unacceptably low return. To me, “I need more upside potential because I’m afraid I could lose money” makes an awful lot more sense than “I need more upside potential because I’m afraid the price may fluctuate.” No, I’m sure “risk” is— first and foremost— the likelihood of losing money.

“There’s a big difference between probability and outcome. Probable things fail to happen— and improbable things happen— all the time.” That’s one of the most important things you can know about investment risk.

Quantification often lends excessive authority to statements that should be taken with a grain of salt. [Phil Tetlock makes a similar point in Superforecasting.]

Recognizing Risk

My belief is that because the system is now more stable, we’ll make it less stable through more leverage, more risk taking.

-MYRON SCHOLES

Whereas the theorist thinks return and risk are two separate things, albeit correlated, the value investor thinks of high risk and low prospective return as nothing but two sides of the same coin, both stemming primarily from high prices.

When everyone believes something is risky, their unwillingness to buy usually reduces its price to the point where it’s not risky at all. Broadly negative opinion can make it the least risky thing, since all optimism has been driven out of its price.

Controlling Risk

[An analogy for understanding risk vs. loss]: Germs cause illness, but germs themselves are not illness. We might say illness is what results when germs take hold.

Since usually there are more good years in the markets than bad years, and since it takes bad years for the value of risk control to become evident in reduced losses, the cost of risk control—in the form of return forgone— can seem excessive.

Being Attentive to Cycles

[On increased spending, borrowing, and buying]: All of these things are capable of reversing in a second; one of my favorite cartoons features a TV commentator saying, “Everything that was good for the market yesterday is no good for it today.”

Cycles are self-correcting, and their reversal is not necessarily dependent on exogenous events. They reverse (rather than going on forever) because trends create the reasons for their own reversal. Thus, I like to say success carries within itself the seeds of failure, and failure the seeds of success.

Awareness of the Pendulum

The mood swings of the securities markets resemble the movement of a pendulum. Although the midpoint of its arc best describes the location of the pendulum “on average,” it actually spends very little of its time there.

Very early in my career, a veteran investor told me about the three stages of a bull market. Now I’ll share them with you.

• The first, when a few forward-looking people begin to believe things will get better

• The second, when most investors realize improvement is actually taking place

• The third, when everyone concludes things will get better forever

Thirty-five years after I first learned about the stages of a bull market, after the weaknesses of subprime mortgages (and their holders) had been exposed and as people were worrying about contagion to a global crisis, I came up with the flip side, the three stages of a bear market:

• The first, when just a few thoughtful investors recognize that, despite the prevailing bullishness, things won’t always be rosy

• The second, when most investors recognize things are deteriorating

• The third, when everyone’s convinced things can only get worse

Combating Negative Influences

The biggest investing errors come not from factors that are informational or analytical, but from those that are psychological.

Charlie Munger gave me a great quotation on this subject, from Demosthenes: “Nothing is easier than self-deceit. For what each man wishes, that he also believes to be true.”

Unskeptical belief that the silver bullet is at hand eventually leads to capital punishment. [This is the investing-related best play on words, ever.]

What weapons might you marshal on your side to increase your odds? Here are the ones that work for Oaktree:

• a strongly held sense of intrinsic value,

• insistence on acting as you should when price diverges from value,

• enough conversance with past cycles—gained at first from reading and talking to veteran investors, and later through experience— to know that market excesses are ultimately punished, not rewarded,

• a thorough understanding of the insidious effect of psychology on the investing process at market extremes,

• a promise to remember that when things seem “too good to be true,” they usually are,

• willingness to look wrong while the market goes from misvalued to more misvalued (as it invariably will), and

• like-minded friends and colleagues from whom to gain support (and for you to support). These things aren’t sure to do the job, but they can give you a fighting chance.

Contrarianism

To buy when others are despondently selling and to sell when others are euphorically buying takes the greatest courage, but provides the greatest profit.

–SIR JOHN TEMPLETON

“Buy low; sell high” is the time-honored dictum, but investors who are swept up in market cycles too often do just the opposite. The proper response lies in contrarian behavior: buy when they hate ’em, and sell when they love ’em.

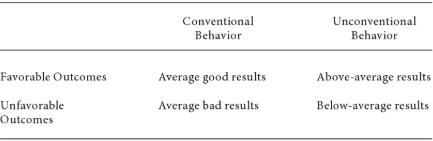

It’s not enough to bet against the crowd. Given the difficulties associated with contrarianism just mentioned, the potentially profitable recognition of divergences from consensus thinking must be based on reason and analysis. You must do things not just because they’re the opposite of what the crowd is doing, but because you know why the crowd is wrong.

Skepticism and pessimism aren’t synonymous. Skepticism calls for pessimism when optimism is excessive. But it also calls for optimism when Skepticism is usually thought to consist of saying, “no, that’s too good to be true” at the right times. But I realized in 2008—and in retrospect it seems so obvious—that sometimes skepticism requires us to say, “no, that’s too bad to be true.”

Finding Bargains

Our goal is to find underpriced assets. Where should we look for them? A good place to start is among things that are:

• little known and not fully understood;

• fundamentally questionable on the surface;

• controversial, unseemly or scary;

• deemed inappropriate for “respectable” portfolios;

• unappreciated, unpopular and unloved;

• trailing a record of poor returns; and

• recently the subject of disinvestment, not accumulation.

To boil it all down to just one sentence, I’d say the necessary condition for the existence of bargains is that perception has to be considerably worse than reality.

Patient Opportunism

The market’s not a very accommodating machine; it won’t provide high returns just because you need them.

–PETER BERNSTEIN

Mujo was defined classically for me as recognition of “the turning of the wheel of the law,” implying acceptance of the inevitability of change, of rise and fall… In other words, mujo means cycles will rise and fall, things will come and go, and our environment will change in ways beyond our control. Thus we must recognize, accept, cope and respond. Isn’t that the essence of investing?

Usually, would-be sellers balance the desire to get a good price with the desire to get the trade done soon. The beauty of forced sellers is that they have no choice. They have a gun at their heads and have to sell regardless of price. Those last three words—regardless of price—are the most beautiful in the world if you’re on the other side of the transaction.

Knowing What You Don’t Know

It’s frightening to think that you might not know something, but more frightening to think that, by and large, the world is run by people who have faith that they know exactly what’s going on.

–AMOS TVERSKY

There are two kinds of people who lose money: those who know nothing and those who know everything.

–HENRY KAUFMAN

[The “I know” school of investors is intellectually arrogant and makes forecasts, the majority of which turn out wrong.] For the “I don’t know” school, on the other hand, the word—especially when dealing with the macro-future—is guarded. Its adherents generally believe you can’t know the future; you don’t have to know the future; and the proper goal is to do the best possible job of investing in the absence of that knowledge.

If you know the future, it’s silly to play defense. You should behave aggressively and target the greatest winners; there can be no loss to fear. Diversification is unnecessary, and maximum leverage can be employed. In fact, being unduly modest about what you know can result in opportunity costs (forgone profits). On the other hand, if you don’t know what the future holds, it’s foolhardy to act as if you do.

Having a Sense for Where We Stand

It would be wonderful to be able to successfully predict the swings of the pendulum and always move in the appropriate direction, but this is certainly an unrealistic expectation. I consider it far more reasonable to try to (a) stay alert for occasions when a market has reached an extreme, (b) adjust our behavior in response and, (c) most important, refuse to fall into line with the herd behavior that renders so many investors dead wrong at tops and bottoms.

You can tell when too much money is competing to be deployed. The number of deals being done increases, as does the ease of doing deals; the cost of capital declines; and the price for the asset being bought rises with each successive transaction. A torrent of capital is what makes it all happen.

Appreciating the Role of Luck

Warren Buffett’s appendix to the fourth revised edition of The Intelligent Investor describes a contest in which each of the 225 million Americans starts with $1 and flips a coin once a day. The people who get it right on day one collect a dollar from those who were wrong and go on to flip again on day two, and so forth. Ten days later, 220,000 people have called it right ten times in a row and won $1,000. “They may try to be modest, but at cocktail parties they will occasionally admit to attractive members of the opposite sex what their technique is, and what marvelous insights they bring to the field of flipping.” After another ten days, we’re down to 215 survivors who’ve been right 20 times in a row and have each won $1 million. They write books titled like How I Turned a Dollar into a Million in Twenty Days Working Thirty Seconds a Morning and sell tickets to seminars. Sound familiar?

The correctness of a decision can’t be judged from the outcome.

Investing Defensively

There are old investors, and there are bold investors, but there are no old bold investors.

[Professional tennis is a “winner’s game”, because the player who can hit the ball where and how they want it most often wins.] The tennis the rest of us play is a “loser’s game,” with the match going to the player who hits the fewest losers. The winner just keeps the ball in play until the loser hits it into the net or off the court. In other words, in amateur tennis, points aren’t won; they’re lost.

Professional tennis players can be quite sure that if they do A, B, C and D with their feet, body, arms and racquet, the ball will do E just about every time; there are relatively few random variables at work. But investing is full of bad bounces and unanticipated developments, and the dimensions of the court and the height of the net change all the time.

Here’s another way to illustrate margin for error. You find something you think will be worth $100. If you buy it for $90, you have a good chance of gain, as well as a moderate chance of loss in case your assumptions turn out to be too optimistic. But if you buy it for $70 instead of $90, your chance of loss is less. That $20 reduction provides additional room to be wrong and still come out okay. Low price is the ultimate source of margin for error.

Avoiding Pitfalls

An investor needs do very few things right as long as he avoids big mistakes.

–WARREN BUFFETT

So most investors extrapolate the past into the future—and, in particular, the recent past. Why the recent past? First, many important financial phenomena follow long cycles, meaning those who experience an extreme event often retire or die off before the next recurrence. Second, as John Kenneth Galbraith said, the financial memory tends to be extremely short. And third, any chance of remembering tends to be erased by the promise of easy money that’s inevitably a part of the latest investment fad.

The success of your investment actions shouldn’t be highly dependent on normal outcomes prevailing; instead, you must allow for outliers.

A portfolio may appear to be diversified as to asset class, industry and geography, but in tough times, nonfundamental factors such as margin calls, frozen markets and a general rise in risk aversion can become dominant, affecting everything similarly.

By definition most people go along with the error, since without their concurrence it couldn’t exist. Acting in the opposite direction requires the adoption of a contrarian position, with the loneliness and feeling of being wrong that it can bring for long periods.

When there’s nothing particularly clever to do, the potential pitfall lies in insisting on being clever.

Adding Value

A manager who earned 18 percent with a risky portfolio isn’t necessarily superior to one who earned 15 percent with a lower-risk portfolio. Risk-adjusted return holds the key, even though—since risk other than volatility can’t be quantified—I feel it is best assessed judgmentally, not calculated scientifically.

Asymmetry— better performance on the upside than on the downside relative to what your style alone would produce—should be every investor’s goal.

Pulling It All Together

The relationship between price and value holds the ultimate key to investment success. Buying below value is the most dependable route to profit. Paying above value rarely works out as well.

My third favorite adage is “Never forget the six-foot-tall man who drowned crossing the stream that was five feet deep on average.” Margin for error gives you staying power and gets you through the low spots.